Pessoa’s family name means “person” in Portuguese, which would have been even more appropriate in the plural-large parts of his oeuvre were produced by other Pessoas. Adopting a different approach, a new, complete edition-published by New Directions, edited by Jerónimo Pizarro and beautifully translated into English by Margaret Jull Costa-dates the entries and publishes them, for the first time, in the chronological order of their writing.īecause of this, the new Book of Disquiet is actually two rather different books, which reflect the shifts in Pessoa’s rather unique authorial strategy. A number of versions (including four in English) have come out since then, and the editors-like Richard Zenith in his 2002 Penguin translation-have generally selected and arranged the entries to give some sense of thematic structure and flow. It took almost fifty years for the first Portuguese edition of The Book of Disquiet to appear in 1982. Pessoa’s enormous, unfinished, and mostly unpublished output must have indeed seemed an infinity to all the scholars who had to sort through the posthumous fragments that were left crammed in trunks at the author’s death in 1935 at the age of forty-seven. But behind this sameness, I secretly scatter my personal firmament with stars and therein create my own infinity.” Drunk on feeling, I drift but never stray. emptier than the void”-and yet, at the same time, everything: “There’s intoxication enough for me in just existing.

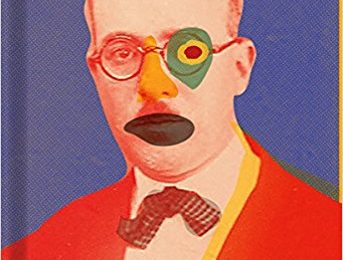

The answer, according to Pessoa, is absolutely nothing-“Life, the soul and the world are all hollow. True to its title, the book perfectly matched my feeling of drifting anomie at a time when work was becalmed, and I found myself wondering, yet again, “Who am I, really?” It’s a peculiarly and often thrillingly adolescent (add Salinger to the above list) way of reading-as-identification-something I rediscovered as I found myself plying the early waves of summer on the bound galleys of Fernando Pessoa’s haunting and fragmentary imaginary diary, The Book of Disquiet. Their thoughts color your days, and your feelings inflect their words, so that it seems as if you are speaking through Thoreau’s Walden ponderings, Dostoevsky’s grand inquisitions, or Proust’s pursuit of lost time. The Book of Disquiet, by Fernando Pessoa, translated by Margaret Jull Costa, New Directions, 468 pages, $24.95Ī few select writers become companions who accompany you on life’s journey, or whatever part of it might coincide with the reading of their books.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)